Netflix Founders' Journey - From DVD Mailers to Global Streaming Giant

January 8, 2026

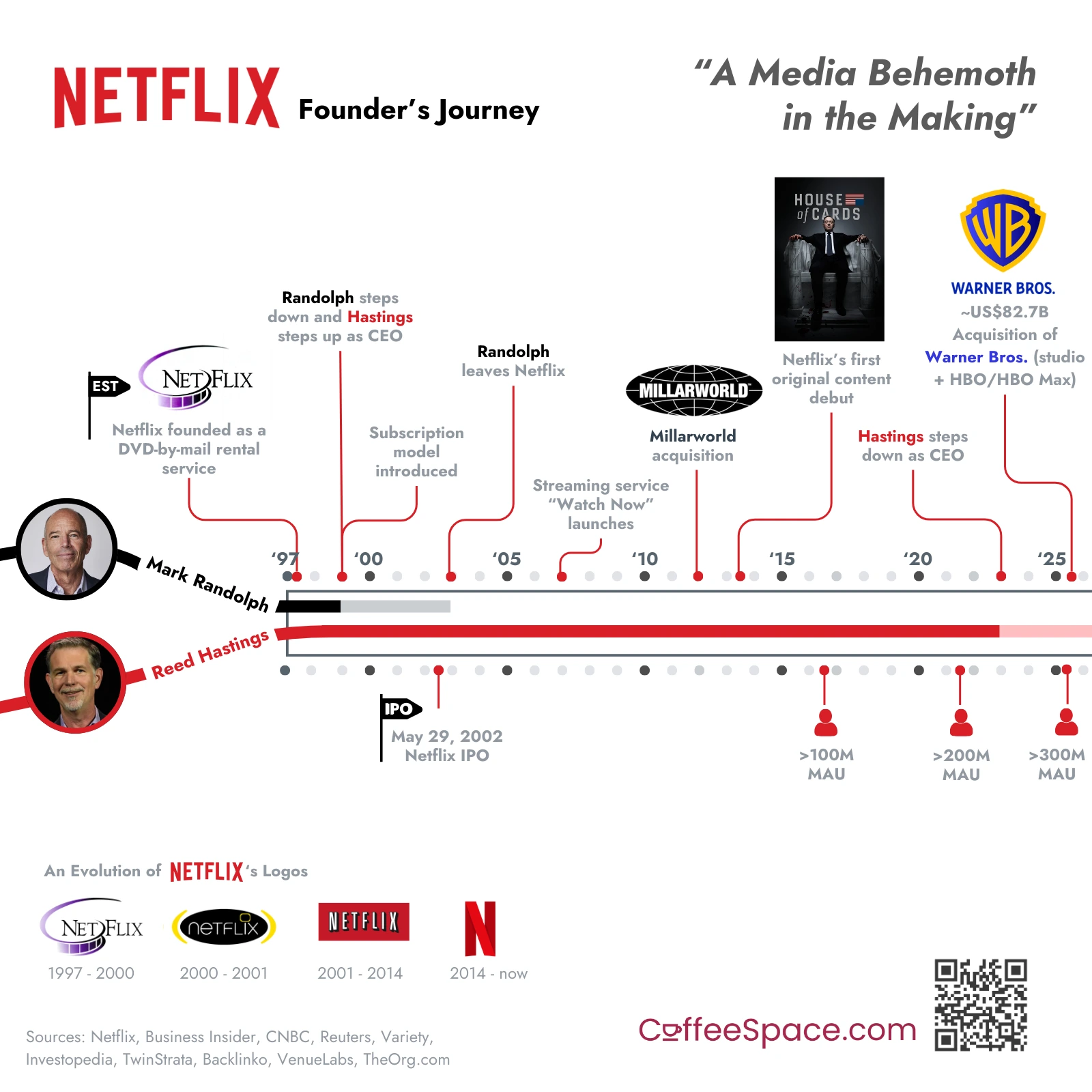

In this edition, we dive into the origins and evolution of Netflix, the company that reshaped how the world consumes entertainment. Join us as we uncover the key milestones, challenges, and lessons learned by Netflix’s co-founders, Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings, on their path to building a global streaming powerhouse.

The story of Netflix begins not in a flashy media office, but in a carpool. In the mid-1990s, Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings — each with backgrounds in software, e‑commerce, and tech — often drove together between Santa Cruz and Sunnyvale, California. Amidst conversation and brainstorming, an idea sparked: what if you could rent movies not from a video store, but from the comfort of your home — by mail?

That idea became real on August 29, 1997: Netflix, Inc. was co‑founded by Randolph and Hastings in Scotts Valley, California. At first, Netflix operated as a DVD-by-mail rental service: customers could order DVDs online, receive them in the mail, and return them after watching — a dramatic rethinking of the traditional video‑rental store.

Netflix’s very first DVD shipment — to a customer in March 1998 — was the 1988 film Beetlejuice. This humble origin made Netflix part of the first wave of digital commerce experimentation: using the Internet to upend an old‑school, physical‑product business model.

The Founders’ Dynamic — Complementary Strengths

- Marc Randolph brought marketing and product‑management chops, having previously co‑founded a mail-order company and worked in software marketing.

- Reed Hastings contributed technical and operational know-how — having been involved in software companies, he understood scalability, systems, and the long view.

Together, they launched a business that offered convenience, avoided late fees, and re‑imagined how people consumed movies.

Early Growth & the Subscription Pivot

Running a DVD mail service came with challenges: shipping logistics, inventory, handling returns. This forced the founders to think hard about sustainability and scalability. Rather than sticking to a per‑rental, pay‑per‑DVD model, they experimented — and in 1999 Netflix introduced a subscription model: for a flat monthly fee, customers could rent “unlimited” DVDs (subject to having a limited number out at once), with no late fees, no due dates, and free shipping. This was a fundamental pivot.

The subscription model did more than simplify revenue forecasting. It aligned Netflix’s incentives with customers’ — encouraging frequent use, loyalty, and retention rather than transactional rentals. This move foreshadowed the recurring‑revenue, subscription‑driven model so common in today’s tech and SaaS world.

Throughout the early 2000s, Netflix steadily scaled its user base. And on May 29, 2002, Netflix completed its IPO, a milestone that not only validated the vision, but gave the company capital to invest in growth.

Meanwhile, Marc Randolph — after playing a critical founding role and shepherding the early years — stepped down as CEO in 1999 (making way for Reed Hastings) and gradually distanced himself from day-to-day operations over the following years.

Under Hastings’ leadership, Netflix built the infrastructure, optimized operations, and prepared for broader transformations.

The Streaming Pivot: From Discs to Digital (2007 Onwards)

By the mid‑2000s, broadband Internet was improving worldwide, and data costs and capacity finally made streaming video more realistic. Hastings and team had long envisioned streaming as the future — some early internal plans even considered a “Netflix box”: a device that could download movies overnight for later viewing.

But by January 2007, Netflix made the bold move: it launched its streaming service, branded “Watch Now.” Subscribers gained the ability to stream video on demand over the Internet — no discs, no mail, no shipping delays. Initially, the streaming library was modest (about 1,000 titles, a fraction of the 70,000+ DVDs available).

This pivot was risky. The DVD business still generated revenue. Data‑delivery infrastructure was unproven. Licensing for streaming was nascent. But Netflix went ahead — cannibalizing its core business to invest in what they believed would be the future of entertainment.

By 2010, Netflix had fully embraced streaming: it introduced standalone streaming-only subscription plans. The “red envelope” days were fading. Over the next few years, Netflix expanded aggressively: launching apps for devices like iPhones and Android phones, partnering with game consoles and smart‑TV manufacturers, and refining its streaming infrastructure (including building its own content-delivery network).

From Distributor to Creator: Original Content & Global Expansion

As streaming took off, Netflix faced a new challenge: relying on licensed content — movies and series owned by studios — exposed it to negotiations, licensing expiration, and competition. The solution? Create its own content.

In 2013, Netflix released House of Cards — its first major original series. That marked a new strategic pivot: Netflix was no longer just a distributor, but a creator.

Original content gave Netflix control: over intellectual property, release timing, distribution, and global rollout. That also meant Netflix could cater to a wide range of audiences — from US viewers to international markets — without needing to license content from others.

Meanwhile, Netflix expanded globally. By 2012, streaming rolled out beyond the U.S.; by 2016, Netflix was available in over 190 countries and territories. The combination of global reach + original content + data-driven recommendation gave Netflix a powerful growth engine.

Changing of the Guard: Leadership and Institutional Evolution

What started as a founder-led startup gradually matured into a global entertainment corporation.

- From 1999 until early 2023, Reed Hastings served as CEO — steering Netflix through major transformations: subscription, streaming, global expansion, original content.

- As Netflix scaled, its leadership structure evolved. The company elevated long-time executive Ted Sarandos (head of content) to co‑CEO status, reflecting content’s central role in Netflix’s identity.

- In January 2023, Hastings stepped down as CEO to become Executive Chairman; Netflix moved to a co‑CEO model under Sarandos and rising executive Greg Peters, combining content strategy with operational/product leadership.

This transition marked Netflix’s shift from a founder-led “move fast, disrupt” company to an institution built to manage global scale, content pipelines, and multi‑modal distribution.

The 2025 Turning Point: Netflix Acquires Warner Bros.

Perhaps the most monumental milestone — not just in Netflix history, but in entertainment industry history — came on December 5, 2025. On that day, Netflix announced a definitive agreement to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery’s studios, streaming business (HBO/HBO Max), and associated libraries — in a deal valuing the assets at US$82.7 billion enterprise value (≈ US$72 billion equity value) after a planned spin-off of WBD’s legacy “linear cable/networks” business.

Under this deal, Netflix stands to gain:

- Legendary film and TV studio infrastructure (Warner Bros. Pictures, New Line, Warner Animation, TV studios, etc.)

- HBO and HBO Max — including their premium content libraries and ongoing production capabilities.

- Iconic and globally recognized intellectual properties and franchises: from DC Comics superheroes to Harry Potter, Game of Thrones–era content, and more — adding enormous cultural capital and IP depth to Netflix's existing slate.

Netflix co‑CEO Greg Peters described the merger as combining “two of the greatest storytelling companies in the world,” promising that this union would vastly expand creative opportunity, global distribution, and value for shareholders.

Simultaneously, Netflix committed to honor theatrical releases for Warner Bros films — signaling an understanding that even in a streaming-dominated era, “event cinema” and big-screen releases remain part of the ecosystem.

The deal is expected to close after WBD completes the spin-off of its traditional cable/networks division (named “Discovery Global”) — expected in Q3 2026.

If approved, this acquisition will transform Netflix from just a streaming + content‑creation company into a fully integrated entertainment super‑platform: owning studios, distribution pipelines, massive IP, and global reach.

Other Strategic Deals & Acquisitions (Pre‑Warner)

Although the Warner Bros acquisition is by far the largest, Netflix had previously begun acquiring companies and IP to build its production capabilities and content ownership. Notable deals include:

- August 7, 2017 — Acquisition of Millarworld: This was Netflix’s first-ever company acquisition, bringing in a library of comic‑book IP from creator Mark Millar, enabling Netflix to adapt comics into shows and films under exclusive ownership.

- September 2021 — Acquisition of Roald Dahl Story Company: Gave Netflix the entire back catalogue of Dahl’s beloved children’s books — allowing development of animations, films, series, games, immersive experiences, and more.

- November 2021 — Acquisition of Scanline VFX (and subsequent integration into visual-effects capabilities): This bought Netflix in-house VFX/post-production capacity, allowing more control over quality, timeline, and costs for its growing content production.

These moves signalled Netflix’s gradual shift from “distributor of licensed content” toward “owner and creator of intellectual property,” laying groundwork for deeper vertical integration long before the Warner acquisition.

What the Warner Bros. Deal Means and Why It’s a Milestone

The 2025 acquisition marks a tectonic shift. Netflix is no longer just a streaming pioneer or content producer — it is becoming a full-spectrum entertainment conglomerate. Some of the immediate and long-term implications:

- Unmatched scale & breadth: With Warner’s studio infrastructure + HBO’s legacy + Netflix’s global distribution + existing originals, Netflix’s content and production library will be deeper and broader than nearly any competitor.

- Full control of production, distribution, IP, and monetization: No longer reliant on licensing from studios or negotiating deals — Netflix will own everything from story creation to distribution to global streaming.

- Stronger moats & competitive edge: Owning iconic IP (DC, Harry Potter, classic films), global distribution, and in-house production — hard for new entrants to replicate.

- Potential for diversified offerings: Beyond films and series — spin-offs, theatrical releases, games, merchandise, global licensing, live events, etc.

- Structural change of the entertainment industry: This is a consolidation move — a sign that “streaming only” is no longer the endgame. The landscape is shifting to vertically‑integrated super‑platforms.

- Signals to creators, talent, and startups: Working with Netflix now means access to huge IP and distribution power — but also means competing with a behemoth. Freelancers, boutique studios may face pressure — but integration could also open new opportunities at scale.

As Netflix itself said in the acquisition announcement: combining two of the greatest storytelling companies in the world could “create greater value for talent” — offering more opportunities to work with beloved IP and reach global audiences.

Founder Lessons

When we trace Netflix’s arc, from a small DVD-mail startup to a global entertainment empire, we see a masterclass in vision, adaptability, timing, and bold risk-taking. Here are some of the key takeaways, especially relevant for founders, entrepreneurs, and startup builders:

1. Start Simple by Solving a Real Pain Point

Netflix began with a clear pain point: the convenience of renting movies minus the hassles — no late fees, no video-store trips, just convenience. The initial idea was simple, concrete, and grounded in real consumer frustration. That kind of clarity is powerful for any startup: find a pain point, solve it elegantly, and build from there.

2. Build Recurring Revenue Early

By shifting to a subscription model (1999) instead of per‑rental fees, Netflix locked in recurring revenue, ensured predictable cash flow, and aligned incentives between the company and its users. For founders, recurring revenue models often create stability, foster customer loyalty, and enable long‑term planning.

3. Don’t Be Afraid to Cannibalize If Long‑Term Value Is Clear

When Netflix launched streaming in 2007, it risked cannibalizing its existing DVD business. But the founders made the hard and correct choice to back the future over the past. For startups, this kind of courage to disrupt your own business before others do can be the difference between leading and being disrupted.

4. Vertical Integration & IP Ownership Build Moats

Relying on licensed content leaves you vulnerable — licensor terms, competition, expiry, and licensing costs. By acquiring IP (Millarworld, Dahl) and building in‑house studios and VFX capabilities, Netflix gained long-term control over content creation, quality, and release cycles. That’s a powerful moat.

6. Leadership Must Evolve — from Founder to Institutional Scale

As Netflix grew, the demands changed. Content strategy, production pipelines, global operations called for a new organizational model. By shifting leadership (co‑CEOs) and elevating domain‑experts (like content heads), Netflix adapted its governance to its scale. Founders must recognize when a company outgrows founder-led startup dynamics and need structures suited for maturity.

If you’re inspired by this story and want to start exploring your own ideas and find someone to get off the ground with, join us at CoffeeSpace.

.png)